(ಸಹಪಾಠಿ ಮಿತ್ರರು ಕಂಡ ಬಾಗಲೋಡಿ ೪)

(ಬಾಗಲೋಡಿ ದೇವರಾಯರ ಸ್ಮರಣ ಸಂಪುಟ – ‘ದೇವಸ್ಮರಣೆ’ ೨೦೦೩ರಲ್ಲಿ ಅತ್ರಿ ಬುಕ್ ಸೆಂಟರ್ ಪ್ರಕಟಿಸಿದ ಪುಸ್ತಕದ ಯಥಾ ವಿದ್ಯುನ್ಮಾನ ಪ್ರತಿ ೨೦೧೭. ಸಂಪಾದಕ – ಜಿ.ಟಿ. ನಾರಾಯಣ ರಾವ್)

(ಭಾಗ ೯)

– K. Raghavendra Rao

The title of this brief journey into the past, into the fabulous mid – 1940s, may sound some what negative but it is really not meant to be so. When I refer to a wasted genius, what I mean is the gap between potentiality and actuality, possibility and reality. Deva Rao was a genius, and I am using that term without reservation, and the full flowering of that genius did not take place for reasons over which Deva Rao himself had very little control. I shall return to this point later and right now let me begin at the begining, my first encounter of him.

The title of this brief journey into the past, into the fabulous mid – 1940s, may sound some what negative but it is really not meant to be so. When I refer to a wasted genius, what I mean is the gap between potentiality and actuality, possibility and reality. Deva Rao was a genius, and I am using that term without reservation, and the full flowering of that genius did not take place for reasons over which Deva Rao himself had very little control. I shall return to this point later and right now let me begin at the begining, my first encounter of him.

When I joined the BA (Honours) course in English language and literature at Madras Christian College, Tambaram, in 1945, Deva Rao was already there in the second year of that three-year course. Even before I physically faced him, I had already heard about him as a legend. His contemporaries at the college referred to him with awe as a brilliant thinker and a master of English language, both spoken and written.

There were stories about his incredible intellectual feats such as how his teachers were scared of his command over the entire terrain of English literature and his dazzling insights into the works of major figures in literature. I was told that he had read virtually every significant work of English literature on his own even before he had joined the honours course! Naturally all this whetted my desire to see the phenomenon in flesh and blood.

In those days third year and fourth honours classes were combined for some papers, and thus I had occasion to sit in the same class as Deva Rao. My first sight of him was a bit dampening. He was physically unimpressive – short, frail, pale, white, his hair unkempt, his dress consisting of a khadi lungi and shirt, both white. But his eyes were sharp, and he had long nails. He sat usually in one of the back seats, and drummed the desk with his long finger nails while the teacher went on lecturing. When drumming stopped, it meant that the teacher had to tackle some complicated, knotty issue that Deva Rao flung at his Guru. The teacher invariably confessed his inability to answer the query raised by Deva Rao and promised the class that he would come back with some answer in his next class!

Now this is likely to be misinterpreted as my friend’s cheap stunt to show off, to indulge in oneupmanship! This was not true because Deva Rao opened his mouth only when some really serious and important issue was at stake. And the teachers concerned took these interventions as creative stimulants that raised the intellectual level of the class-room discourses. I recall particularly one such intervention during GC Martin’s lectures on the Elizabethan dramatist Webster. Martin was an excellent teacher and a fine human being. His next lecture was wholly devoted to the point raised by Deva Rao. While Rao was fierce during discussions and debates, he was a very gentle creature after the acrimonious hairsplitting intellectual fights, and flights too.

I remeber that he was obsessed with big words, and took a wicked delight in using words, both long and obscure, sending the listner often to ransack dictionaries. In fact, he wrote a short essay for the college magazine, entitled, In Defence of Big Words. He was full of such endearing angularities and behavioural oddities. He also enjoyed being an odd man out, taking positions directly opposed to that of the herd! For instance, it was axiomatic that a student must read AC Bradley’s book on Shakespearean tragedies to negotiate the paper. But Deva Rao openly and aggressively vowed never to touch Bradley and still do well in the paper on Shakespeare in the final examination. As a matter of fact, he scored distinction in that paper without the help of Bradley!

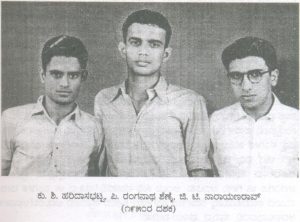

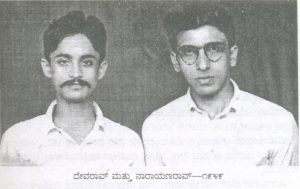

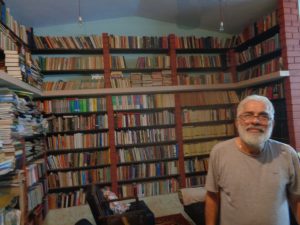

We, the Kannadigas, on the campus were a small and intimate group, mostly hailing from Kodagu, Bellary and Dakshina Kannada districts. During my time, it included such future luminaries as Haridasa Bhat, Namiraja Malla, Ranganath Shenoy, Kushalappa and GT Narayana Rao. In the English department, there was another distinguished Kannadiga student, M Panchappa, who was one year senior to Deva Rao. We were a close-knit group and Deva Rao was like a focal point of our collective life. I have pleasant memories of long evening walks in his company, and his eloquent and passionate denunciation of God and other cherished beliefs. I think he was a Congress Socialist weekly, Janata, and drew my attention especially to its lively, satirical column, Calibindia. His intellectual enthusiasm was infectious, and we were constantly nudged by him to read this book or that book. I became an addict to book-reading through the combined influence of Deva Rao and Panchappa, an addiction which I have not been able to shake off even now at the age of 75!

We, the Kannadigas, on the campus were a small and intimate group, mostly hailing from Kodagu, Bellary and Dakshina Kannada districts. During my time, it included such future luminaries as Haridasa Bhat, Namiraja Malla, Ranganath Shenoy, Kushalappa and GT Narayana Rao. In the English department, there was another distinguished Kannadiga student, M Panchappa, who was one year senior to Deva Rao. We were a close-knit group and Deva Rao was like a focal point of our collective life. I have pleasant memories of long evening walks in his company, and his eloquent and passionate denunciation of God and other cherished beliefs. I think he was a Congress Socialist weekly, Janata, and drew my attention especially to its lively, satirical column, Calibindia. His intellectual enthusiasm was infectious, and we were constantly nudged by him to read this book or that book. I became an addict to book-reading through the combined influence of Deva Rao and Panchappa, an addiction which I have not been able to shake off even now at the age of 75!

Surely it is an irony of historty that young men and women who belonged to the generations involved in fighting British Imperialism should rush to become bureaucrats after independence by joining the IAS, IFS and other Administrative services. Virtually, all my contemporaries at Tambaram during the years immediately following Independence took the competetive examination and most of them successfully completed it. These brilliant men like Deva Rao or Panchappa, who could have made outstanding contribution to our cultural and intellectual life as scholars, teachers and journalists, found themselves sucked into the belly of bureaucracy. One reason certainly was that teaching was very badly paid in comparison with administrative services. It was perhaps inevitable that Deva Rao, too, joined the crowd, wrote the examination and got selected for the prestigious Indian Foreign Service.

Surely it is an irony of historty that young men and women who belonged to the generations involved in fighting British Imperialism should rush to become bureaucrats after independence by joining the IAS, IFS and other Administrative services. Virtually, all my contemporaries at Tambaram during the years immediately following Independence took the competetive examination and most of them successfully completed it. These brilliant men like Deva Rao or Panchappa, who could have made outstanding contribution to our cultural and intellectual life as scholars, teachers and journalists, found themselves sucked into the belly of bureaucracy. One reason certainly was that teaching was very badly paid in comparison with administrative services. It was perhaps inevitable that Deva Rao, too, joined the crowd, wrote the examination and got selected for the prestigious Indian Foreign Service.

When he came to Tambaram from AC College of Technology where he was teaching English, to appear for the interview before the UPSC, he did not know how to wear a tie! And I remeber it was I who helped him put on the tie. A person of Deva Rao’s independent spirit and original mind would not be a success in a system dominated by sycophancy and nepotism. As a diplomat, Deva Rao never saw service in major countries, being mostly offered insignificant assignments.

Before I finish with this part of the story, I have a confession of guilt to make, something worrying me all my life. When Deva Rao was briefly asked to leave service on medical grounds and was told that he could re-join after making himself medically fit, he was resting at home trying to return to normal health. At that time I was teaching English at a college in Mambalam in Madras. One day I got a post card from him, requesting me for a small amount of money as loan, needed for buying medicine. The amount involved was not much, certainly not beyond my resources. I am by nature not an inconsiderate person, and Deva Rao was a good friend. Even to this day it remains a mystery to me why I did not send that money. My sense of guilt was intensified when I heard a few months after getting his card that he had attempted to commit suicide! I can never forgive myself, though Deva Rao himself forgave me for it when, years later, I saw him in New Delhi, where he was then working at the External Affairs Ministry as an officer in charge of Pakistan desk.

We had lunch he hosted at the Constitution Club. During the lunch, I raised this matter and asked him to forgive me. But I was in for a shock, not surprise! Deva Rao now advocated belief in God with the same passion and intellectual aggression with which he used to demolish God and belief in Him. He had now become a fatalist, a believer in gods and goddesses, the favourite being the Godess at Kateel in his native district. Deva Rao not only forgave me, he declared that there was nothing to forgive as our actions were mostly beyond our control! I was, of course, prepared for his forgiving me but certainly not prepared for the reason offered for it! The transformation was both physical and personality-wise. He had put on more flesh and dressed stylishly with diplomatic elegance. That was the last I saw of him.

Now reflecting on that meeting, I wonder whether I am right in holding that he was transformed at all! What I mean is that there was no fundamental transformation of the person but merely a change at the surface level, a change merely in the externalities. Whether he was demolishing god or whether he was surrendering to fate, it was the same intense, passionate and living, throbbing person. I know of none who lived as intensely as Deva Rao. Whatever he did was done with the same total immersion, relentless commitment.

The story of our relationship has a sequel. When I shifted to Konaje to teach at Mangalore University in the 1980s, I read about Deva Rao’s return to Bangalore after retiring. I was hoping to rope him in as an Honorary Director of a Centre for Diplomatic studies as part of Mangalore University. I even talked about this to his nephew and colleague, Surendra Rao, the historian. But before I could do anything about it or even before I could meet Deva Rao, I was shocked to read that he had died after a massive heart attack. It was a loss not merely to his immediate family and his close friends but to Karnataka and the country. It is almost certain that he would have resumed the brilliant creative work he had briefly attempted in his fascinating short stories. These stories reveal a flair for seeing the fantastic side of the ordinary life in the manner of Calvin but without sliding wholly into fantasy. I am sure he would have enriched the intellectual and cultural life of Karnataka. But all this was not to be. We can only mourn his loss and regret the not happening of what could have been! I am sure that, like me, all those friends who had entered the orbit of his flaming life, however briefly, will consider themselves fortunate to have known this strange person of real genius. Salute to you, good friend, wherever you are now, and I can never forget you!

I was told by Surendra Rao that when he referred to me during last months of his life, Deva Rao remembered me as a poet! Well, at least to justify that title he gave me, ironically or otherwise, I yield to the temptation to end this note with a brief lyrical tribute. By the way, I use the term, ironical, here because Deva Rao always tended to be mystified and uneasy in the presence of poetry!

I was told by Surendra Rao that when he referred to me during last months of his life, Deva Rao remembered me as a poet! Well, at least to justify that title he gave me, ironically or otherwise, I yield to the temptation to end this note with a brief lyrical tribute. By the way, I use the term, ironical, here because Deva Rao always tended to be mystified and uneasy in the presence of poetry!

Farewell, friend, on your departure,

From where we honour and suffer mortality,

But more than farewell, we thank you for the gift

Of your life, for sharing your sight and insight,

Feasting on your feverish flights

Into spaces our eyes can hardly measure –

Thanks, too, for the story of your life

And its enigma, its illumination and its ironies!

(ಮುಂದುವರಿಯಲಿದೆ)

Apt tribute to the companion who was a genius! Yes,to face such repentence in our lives hurts beyond words.

It was a pleasure to read Dr Raghavendra Rao on Deva Rao. As always, Prof. Rao writes straight from the shoulder, but with an endearing earnestness. As a Marxist scholar, Prof. Rao locates Deva Rao as a man of his times, and that makes reading his piece delightful and instructive. As for Deva Rao's thinking of Prof Rao as a poet, he could be forgiven: only did Prof Rao write some poetry, he was also part of a historic initiative by P. Lal of the Calcutta Writers Workshop to promote Indian Poetry in English. If Prof. Rao is reading this from somewhere, he would be mortified to note that I have put him on our MA English syllabus at Mangalore University. I might then have to seek Prof. Rao's forgiveness, myself! Ravishankar Rao, Professor of English at Mangalore University

Please add the word “not” after the colon in the fourth sentence of my post… (not only did Prof Rao write some poetry, he was also part of…)..

ಕ್ಷಮಿಸಿ ರವಿಶಂಕರ್, ಬ್ಲಾಗರ್ ಅನ್ಯರ ಪ್ರತಿಕ್ರಿಯೆಗಳನ್ನು ‘ಯಜಮಾನನಿಗೆ’ ಕಿತ್ತುಹಾಕಲು (ಡಿಲೀಟ್) ಅವಕಾಶಕೊಡುತ್ತದೆ (ಅದು ನಾ ಮಾಡುವುದಿಲ್ಲ), ತಿದ್ದಲು ಕೊಡುವುದಿಲ್ಲ. ಹೇಗೂ ತಿದ್ದುಪಡಿ ನೀವು ಸೂಚಿಸಿದ್ದೀರಲ್ಲ ಸಾಕು. ನಿಮ್ಮ ಪ್ರತಿಕ್ರಿಯೆ ತೂಕದ್ದು, ಬೇಕು. ಕೃತಜ್ಞ.

ನಮಗೂ ಅರ್ಥವಾಗುವಷ್ಟು ಸರಳ ಇಂಗ್ಲಿಷ್… ಉತ್ತಮ ಬರಹ.